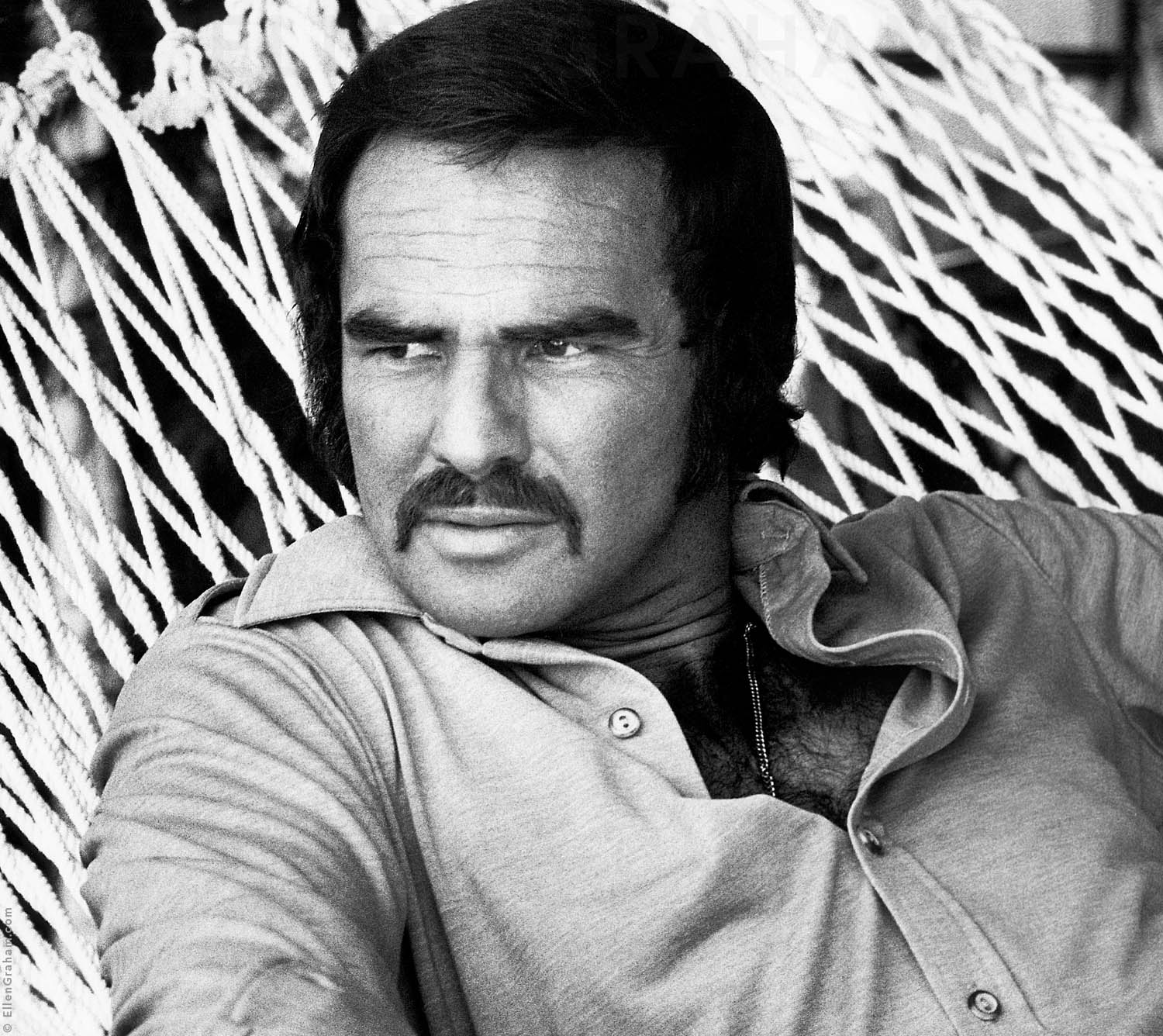

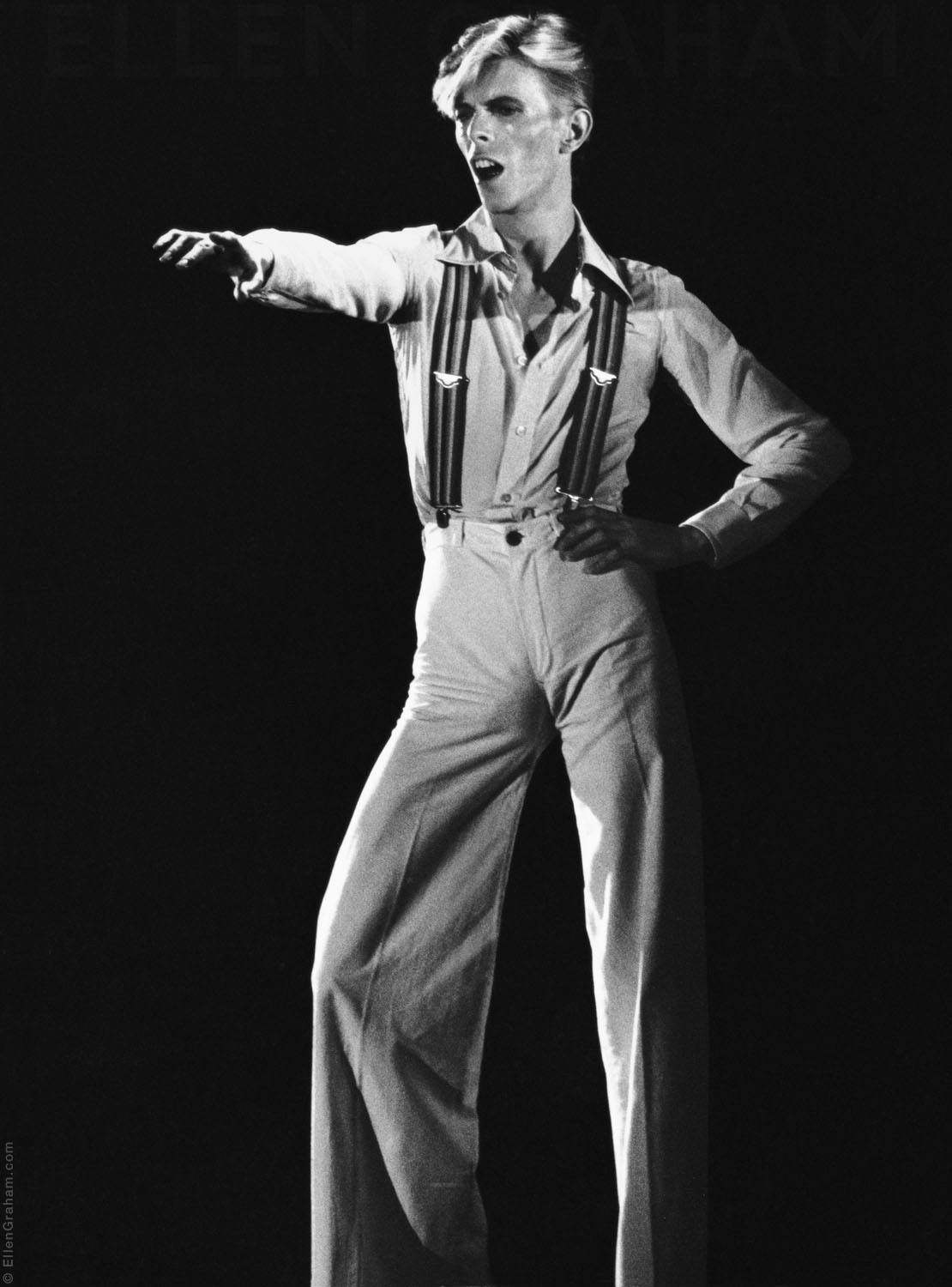

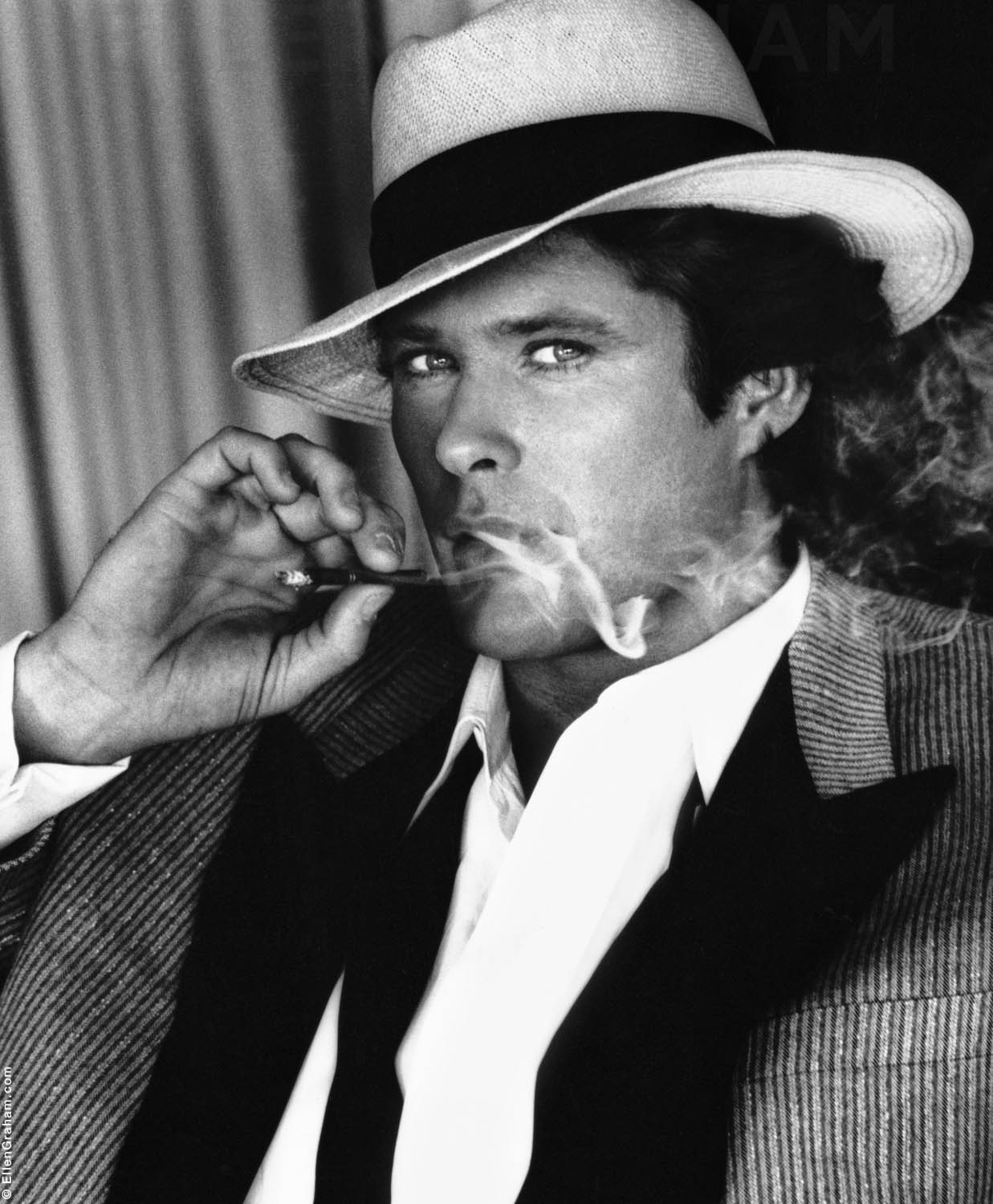

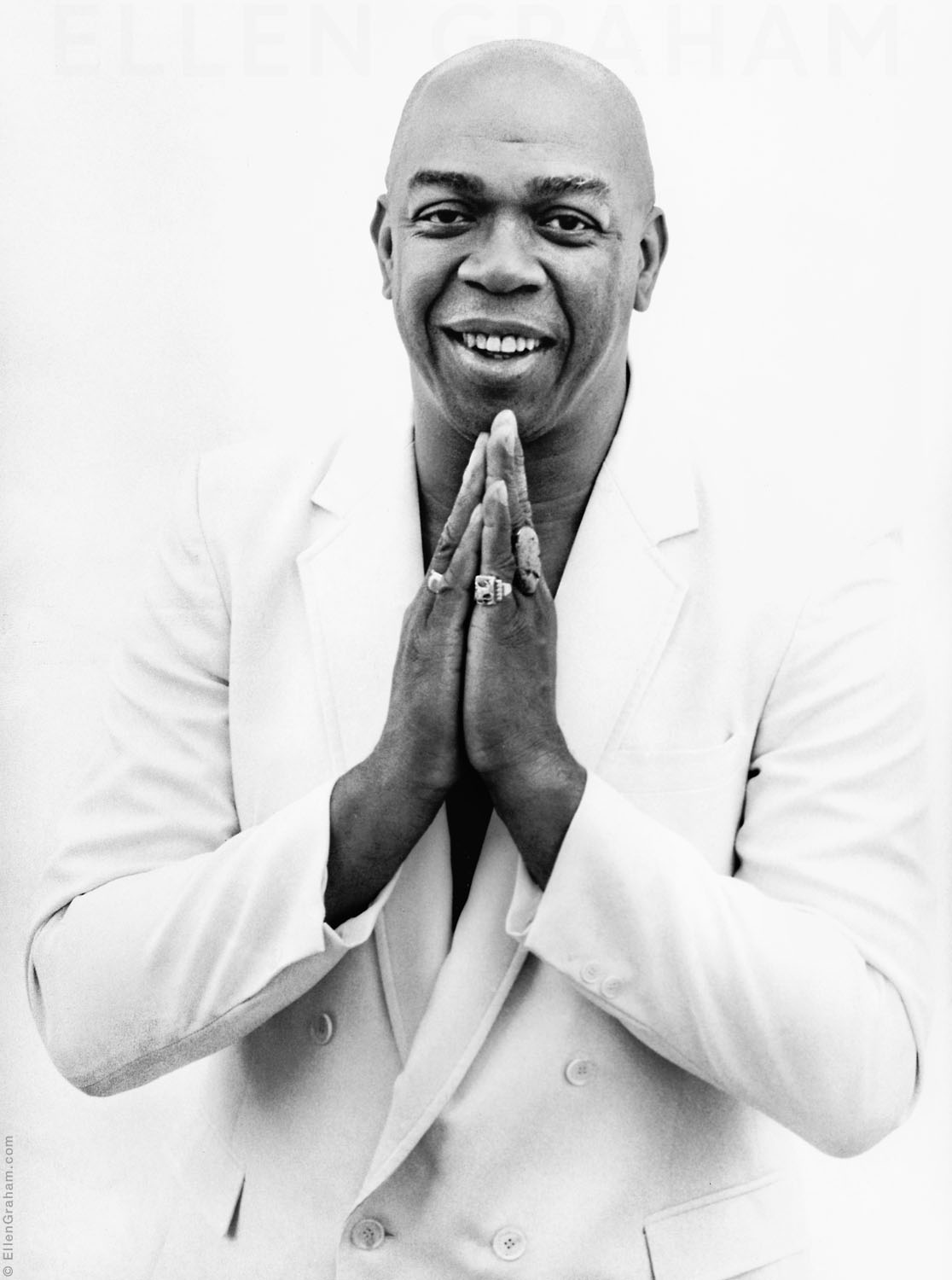

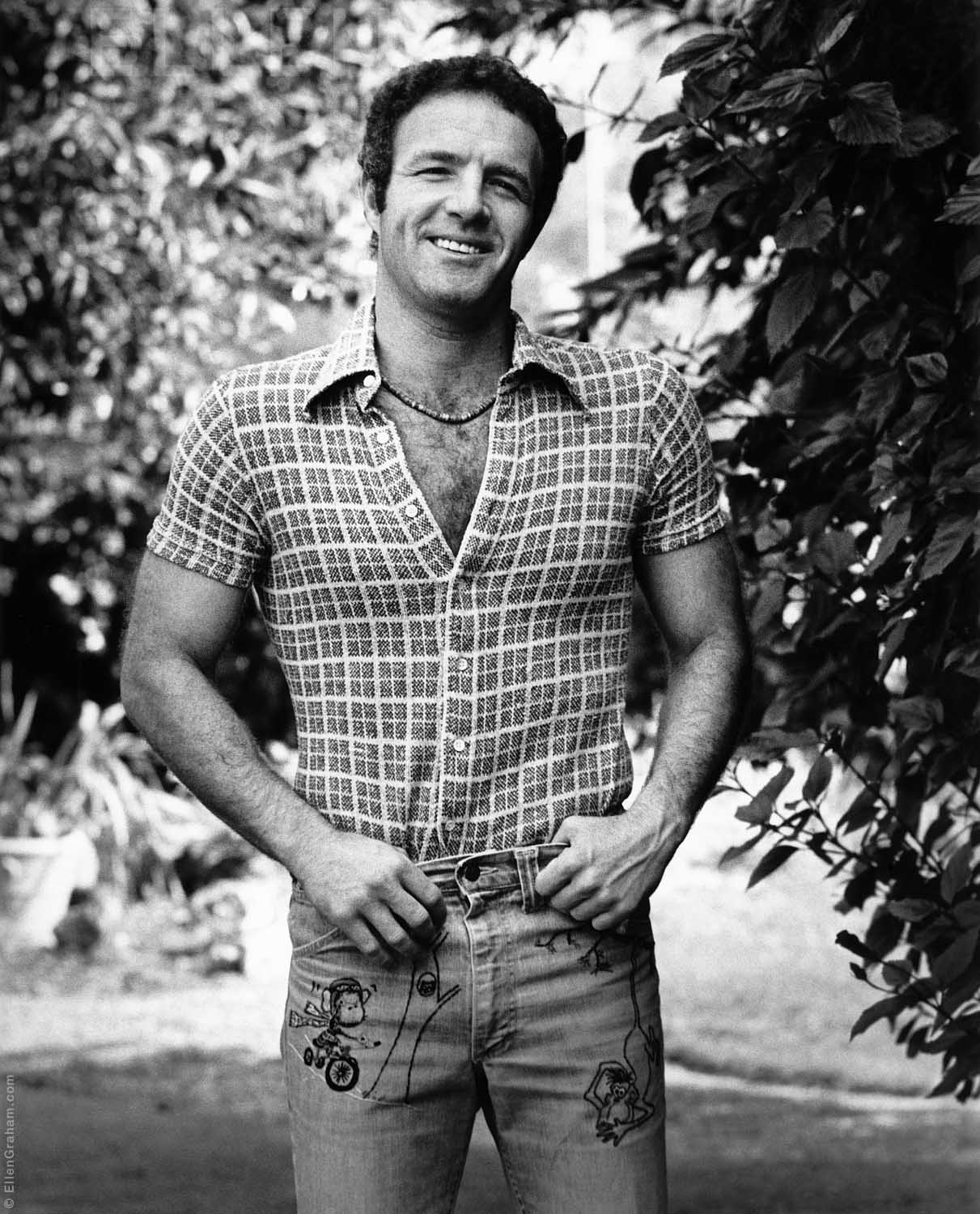

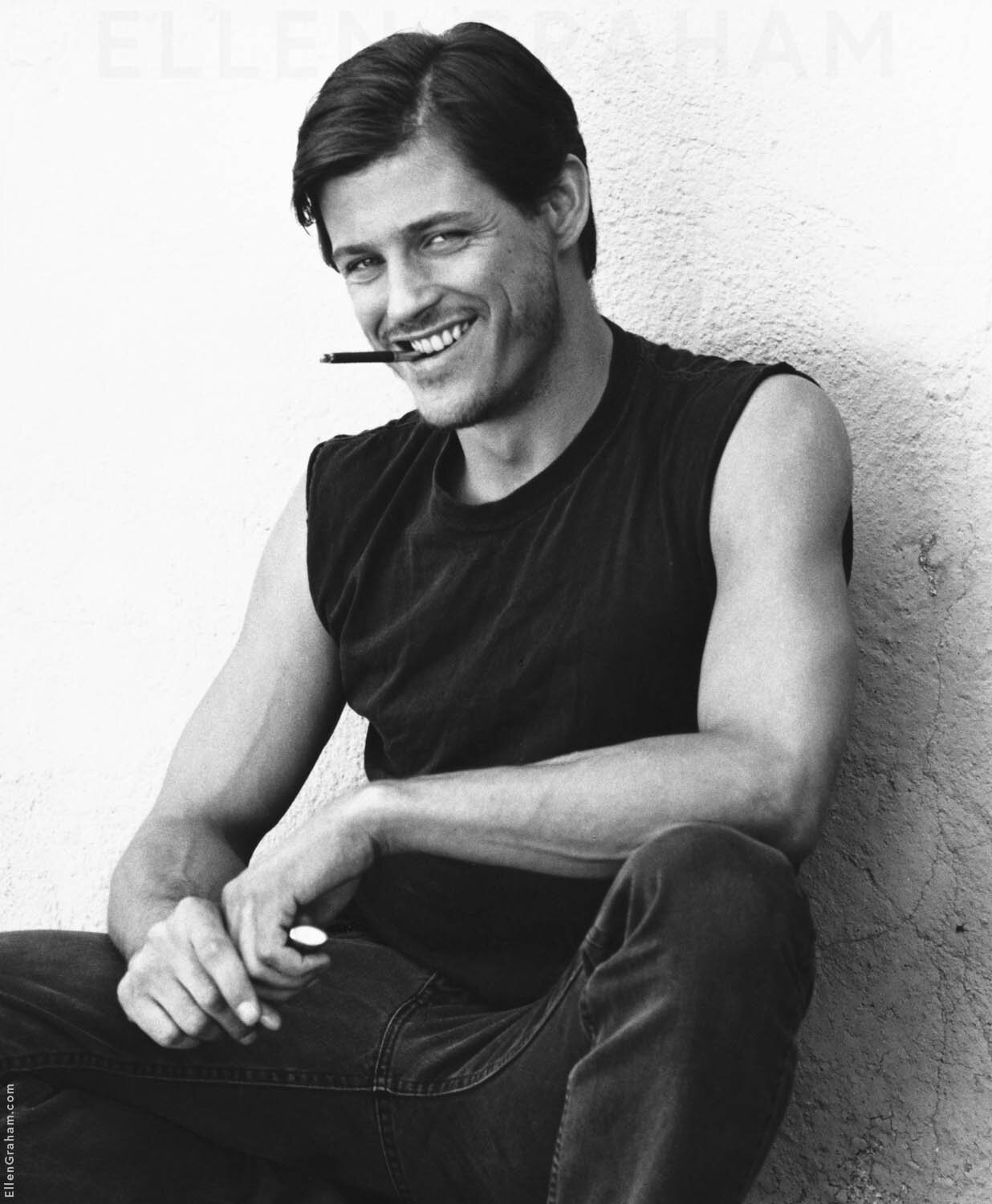

Beautiful Men Project, 1970’s-80’s

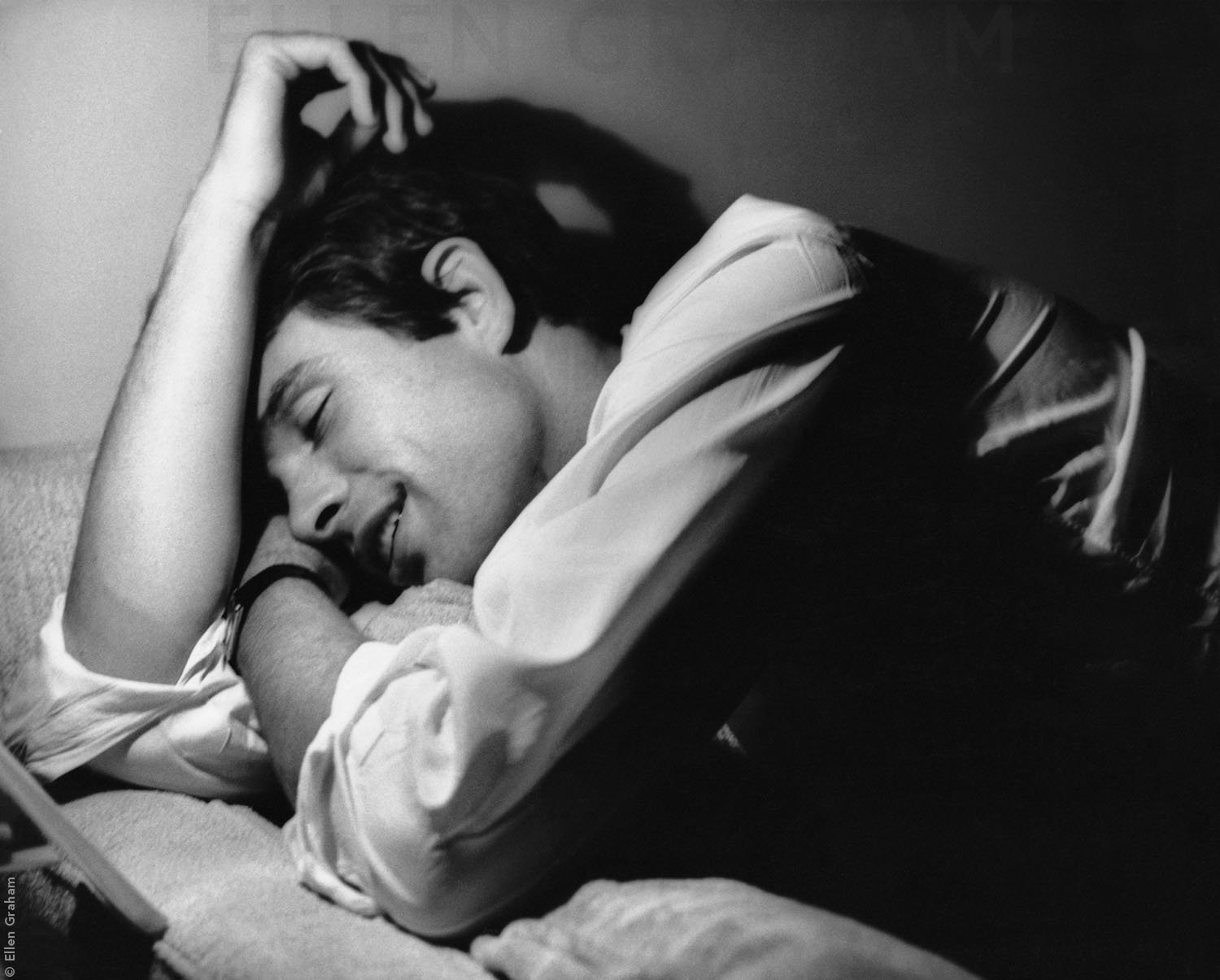

“I think that there has never been a book like [Beautiful Men] before because women were always sex objects and men were buying the books. There were pin-up girls but there were never pin-up boys and I think what suddenly happened is that there has been a reversal and women are interested in seeing men’s bodies.” Ellen Graham, 1984

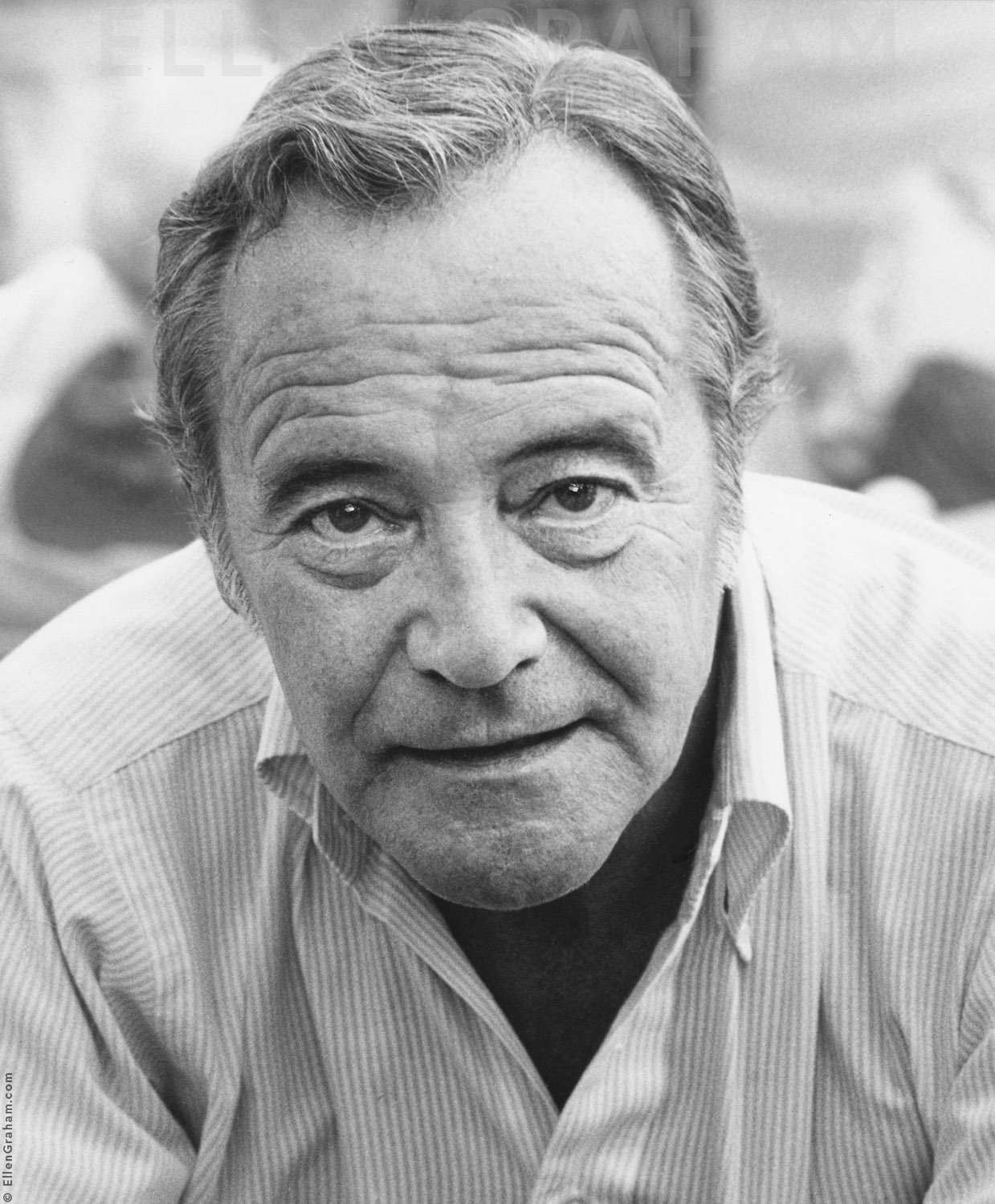

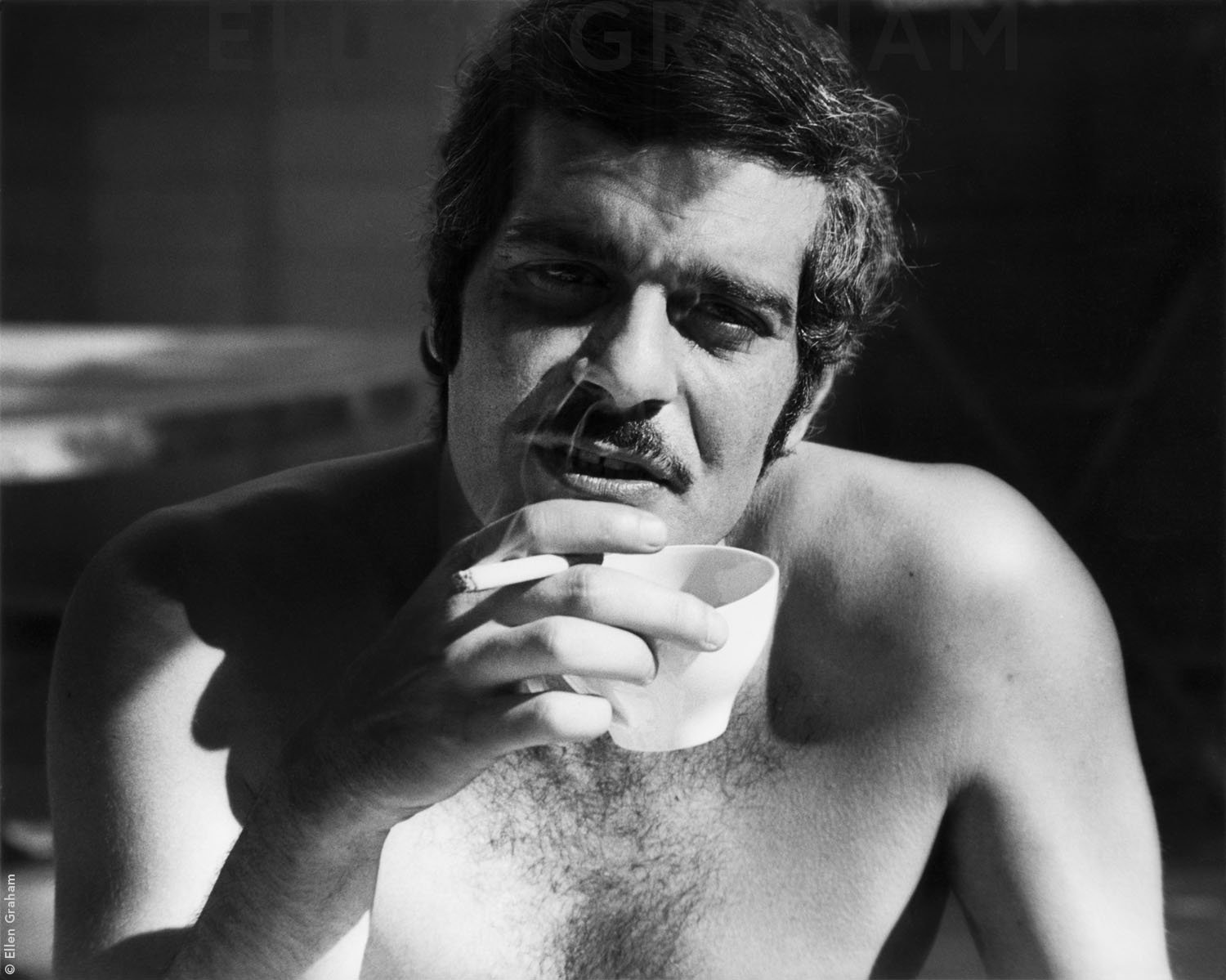

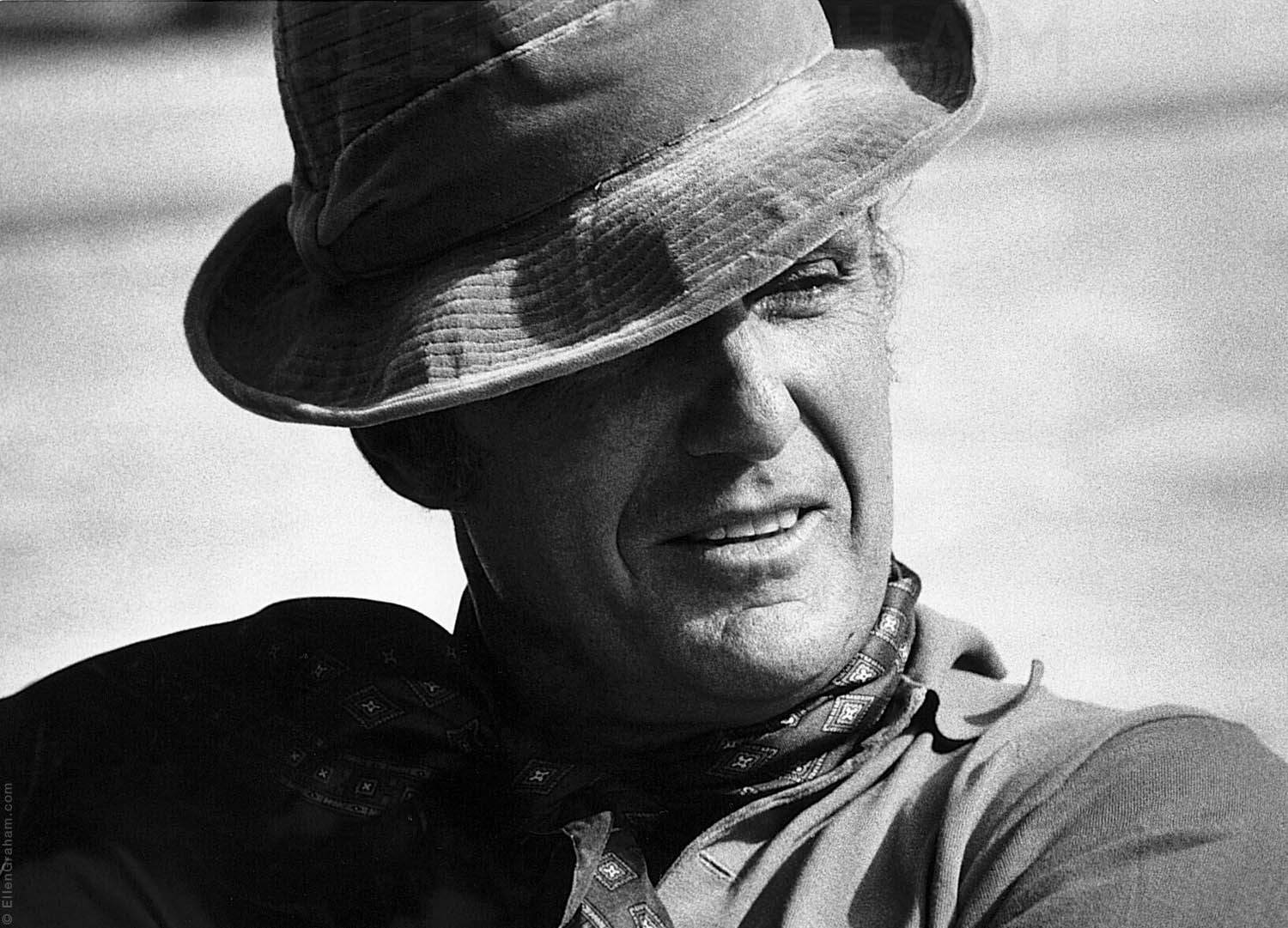

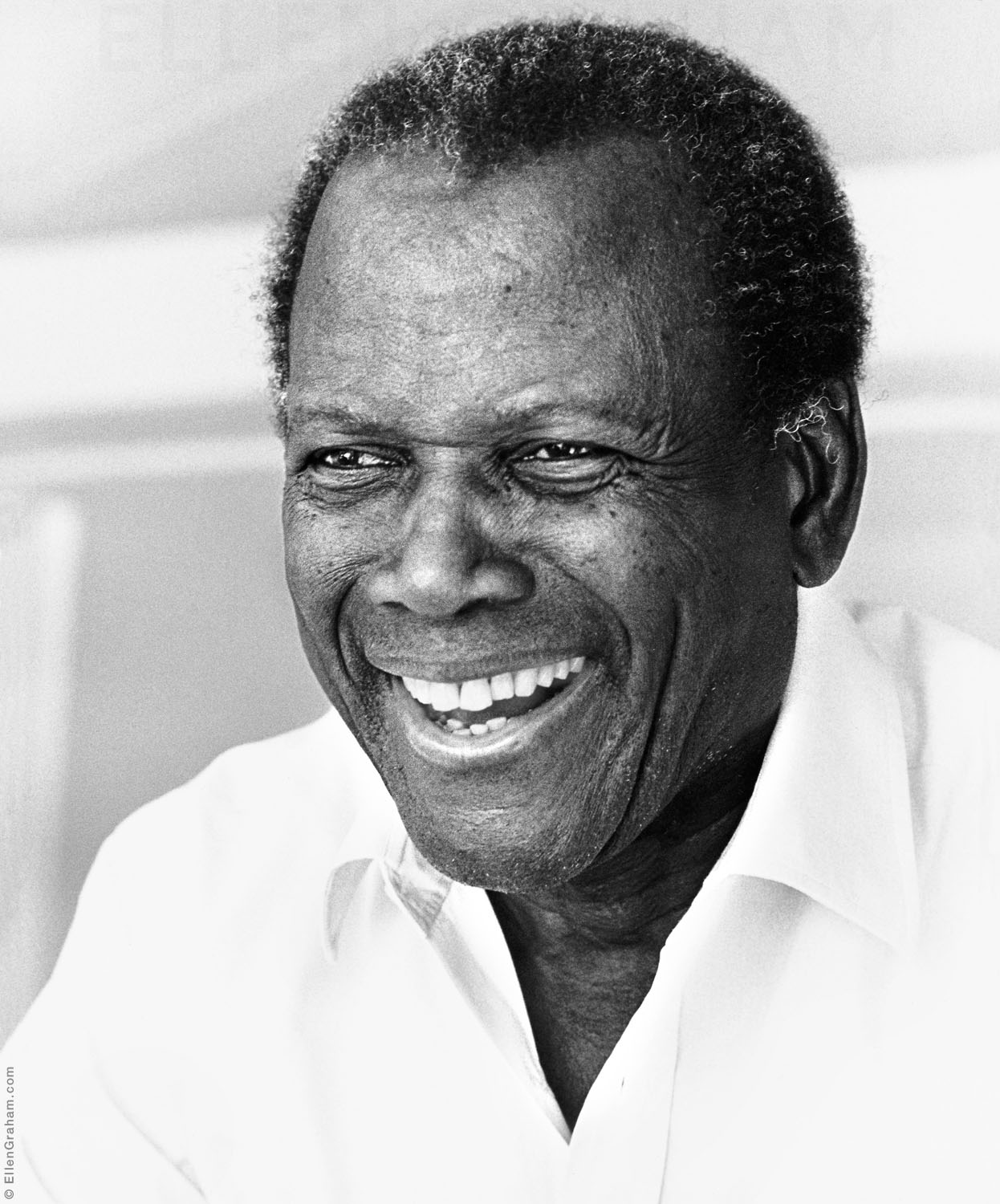

Billy Dee Williams, Beverly Hills, CA, 1983

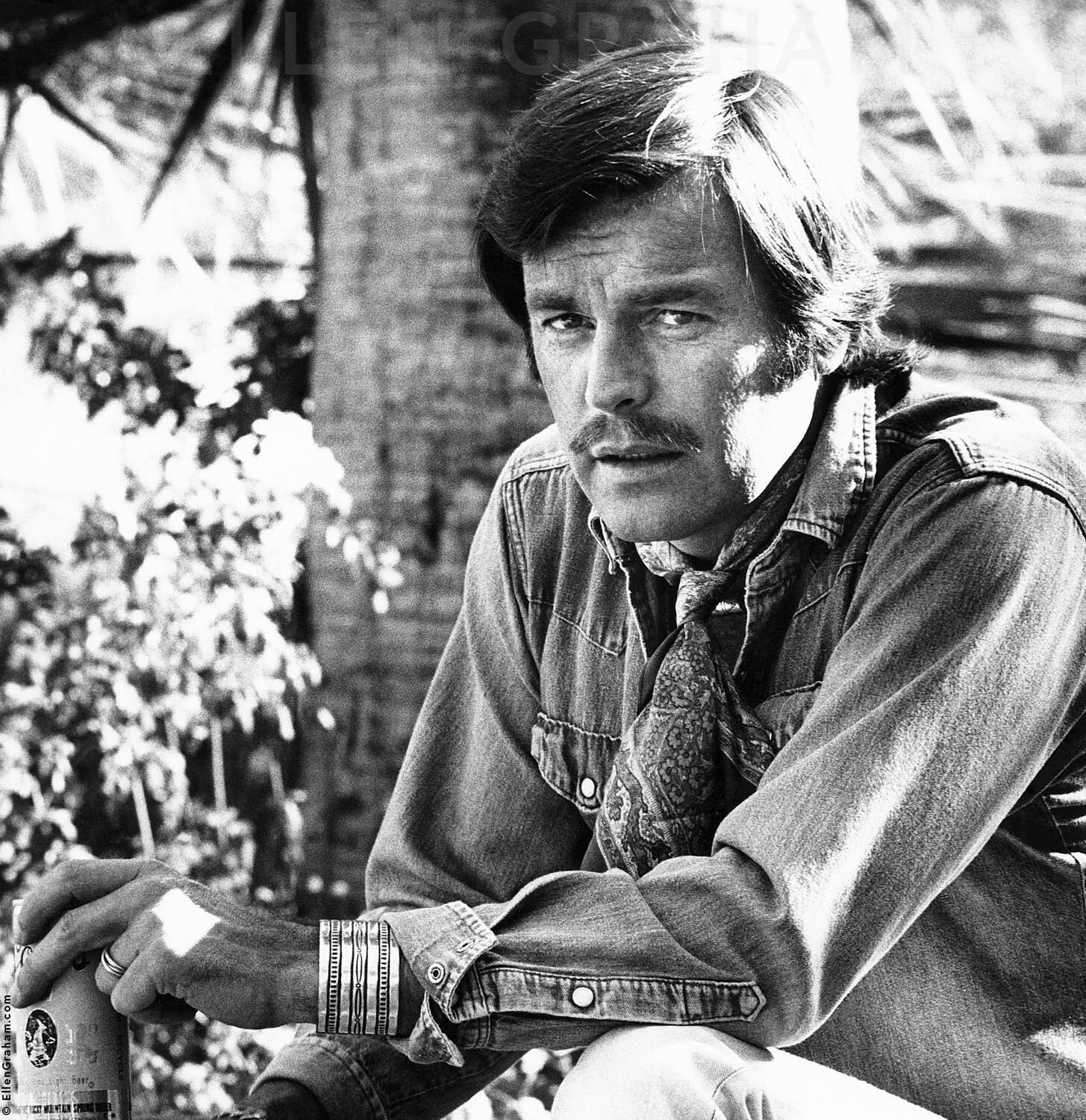

1984

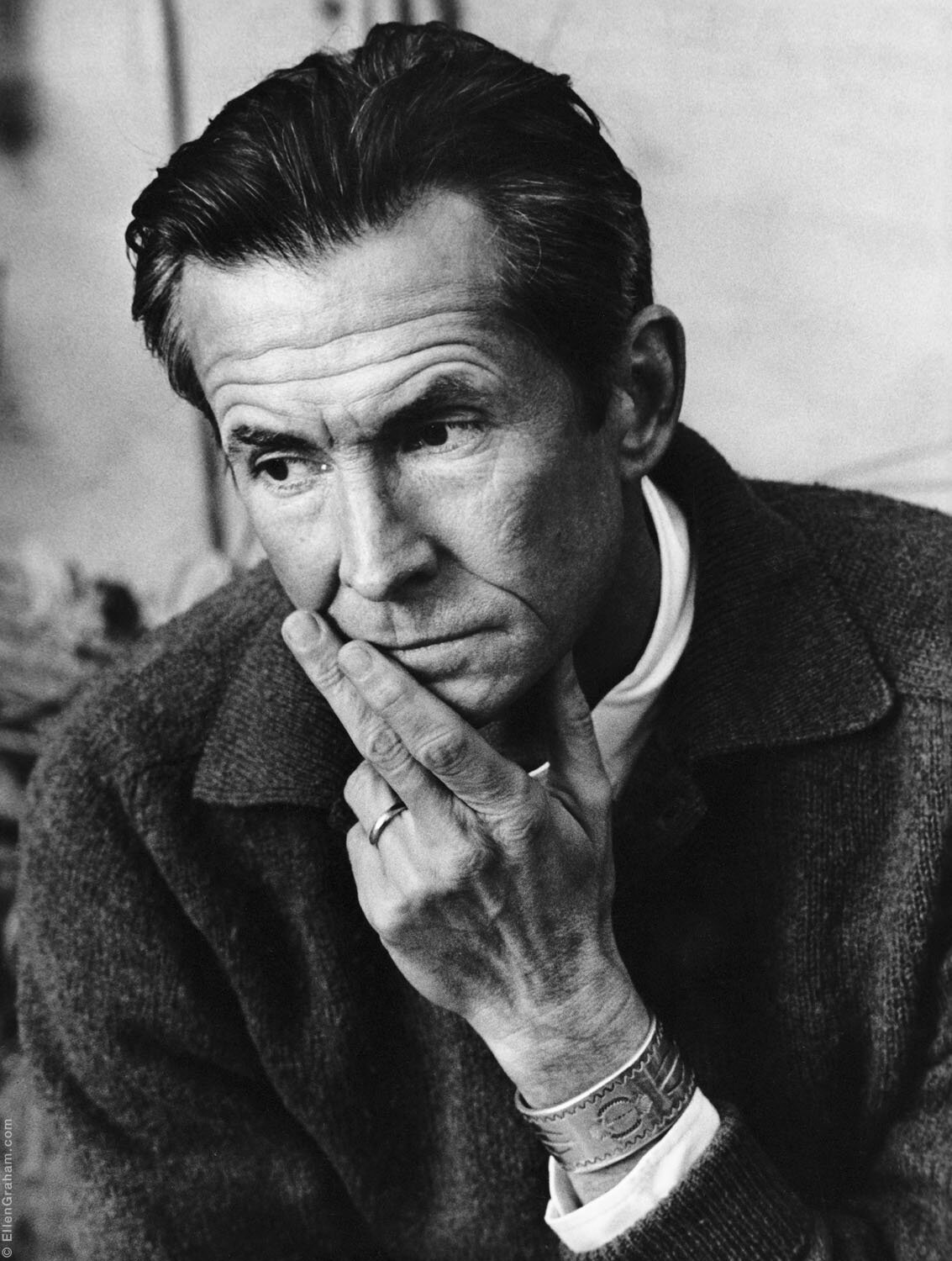

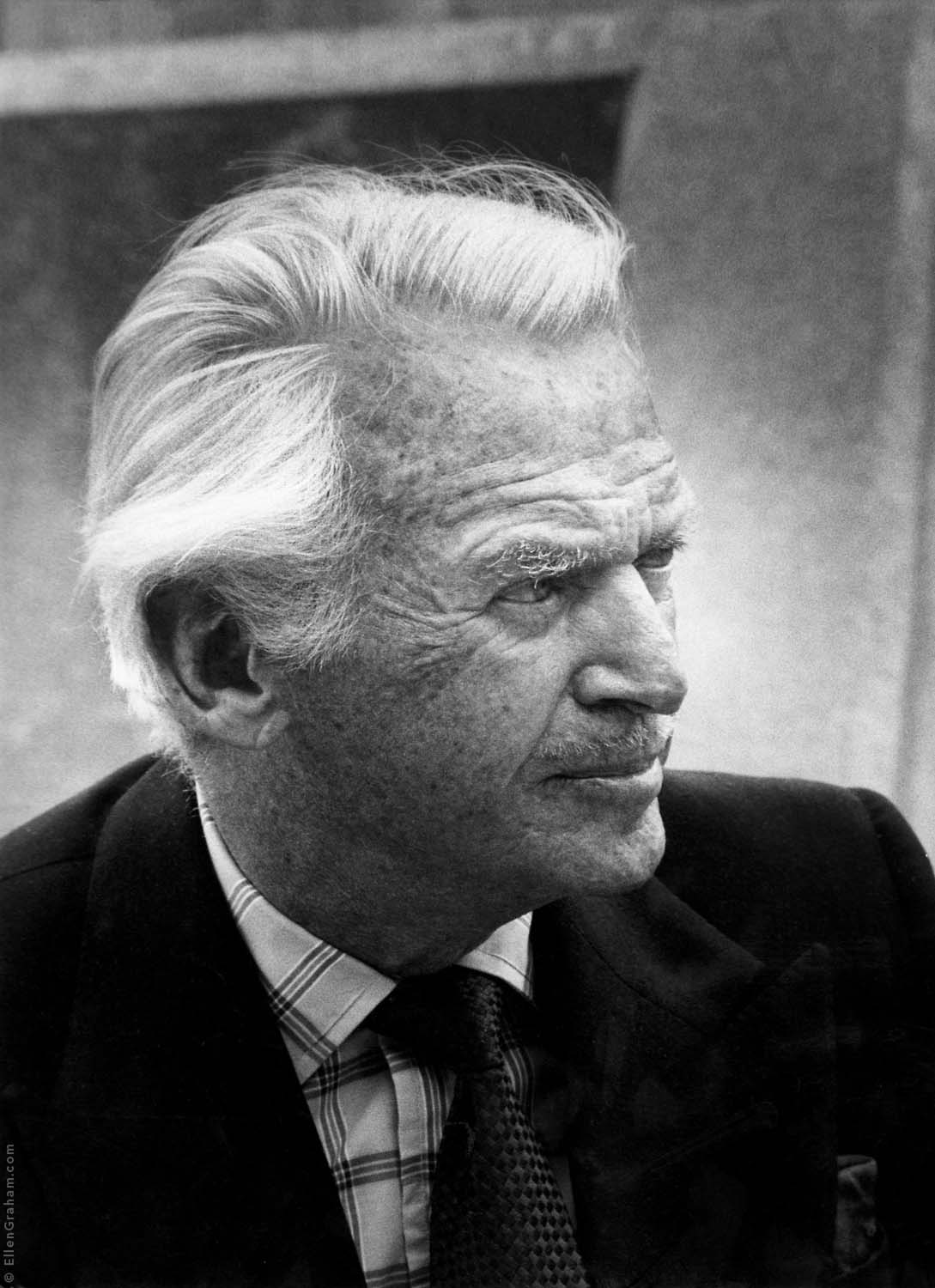

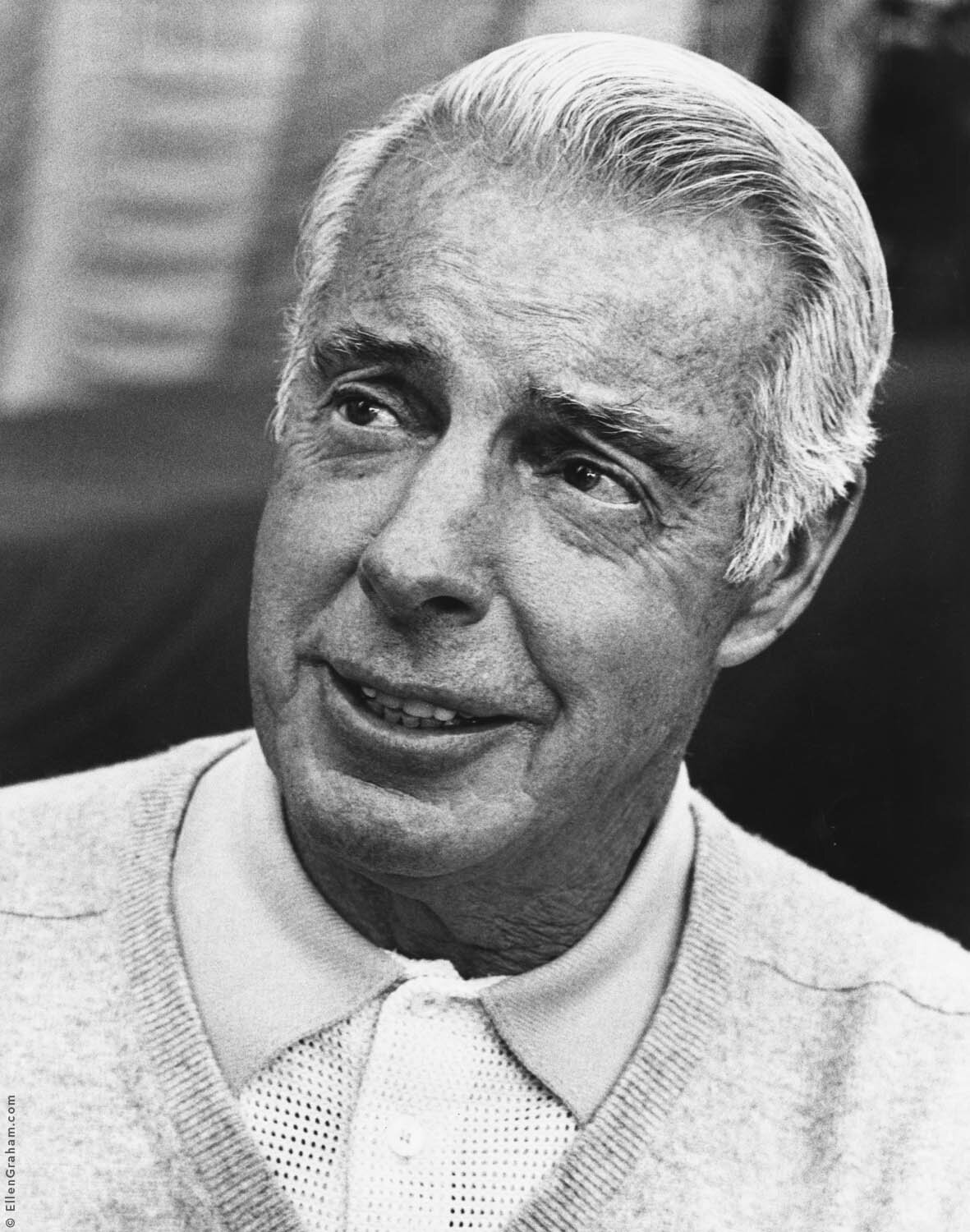

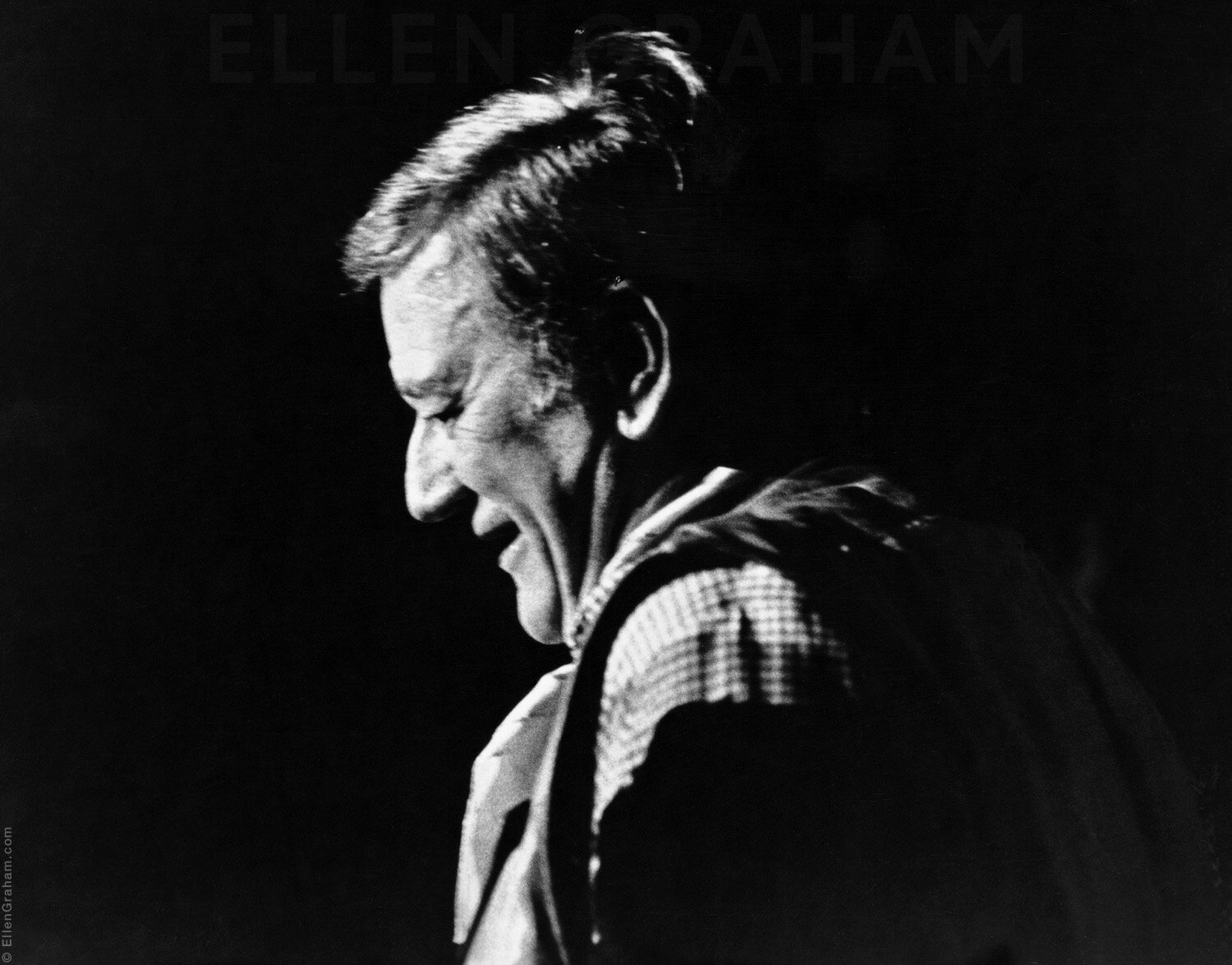

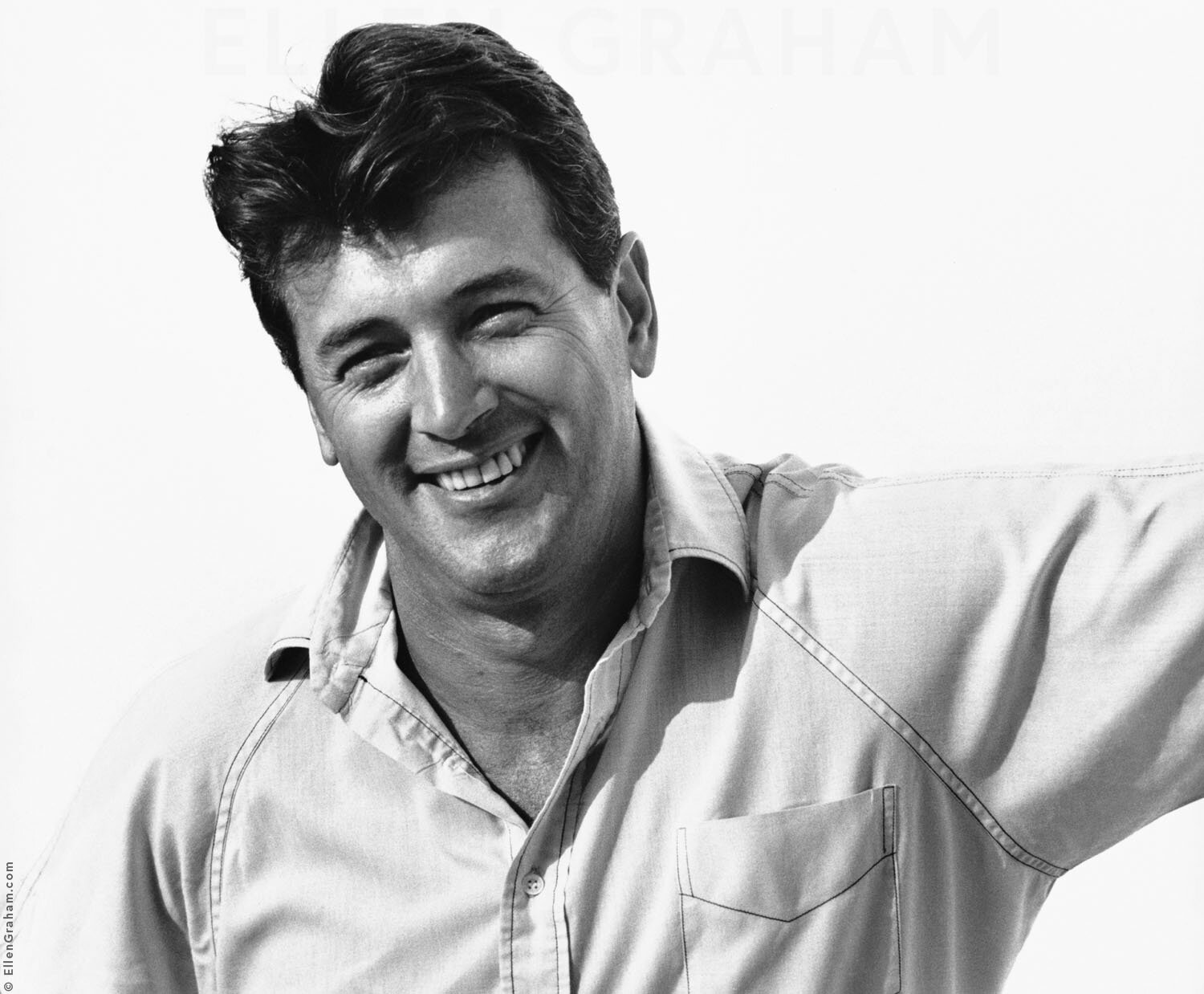

Fred Astaire, Beverly Hills, CA, 1966

For my “Hundred Most Attractive Men in the World” project, I began in 1966 with Fred Astaire. I arrived at his beautiful home in Beverly Hills. I was charmed. Fred was in his sixties, graceful in everything he did, and he was my idol. I told him how much I loved his singing, and he said, “I can’t sing.” I have every recording he ever made.

Exhibition Catalogue Prospectus, Norton Museum of Art 2024

The following is an excerpt about Ellen Graham’s Beautiful Men project from an essay by Lauren Richman, PhD, William and Sarah Ross Soter Curator of Photography, Norton Museum of Art, 2024.

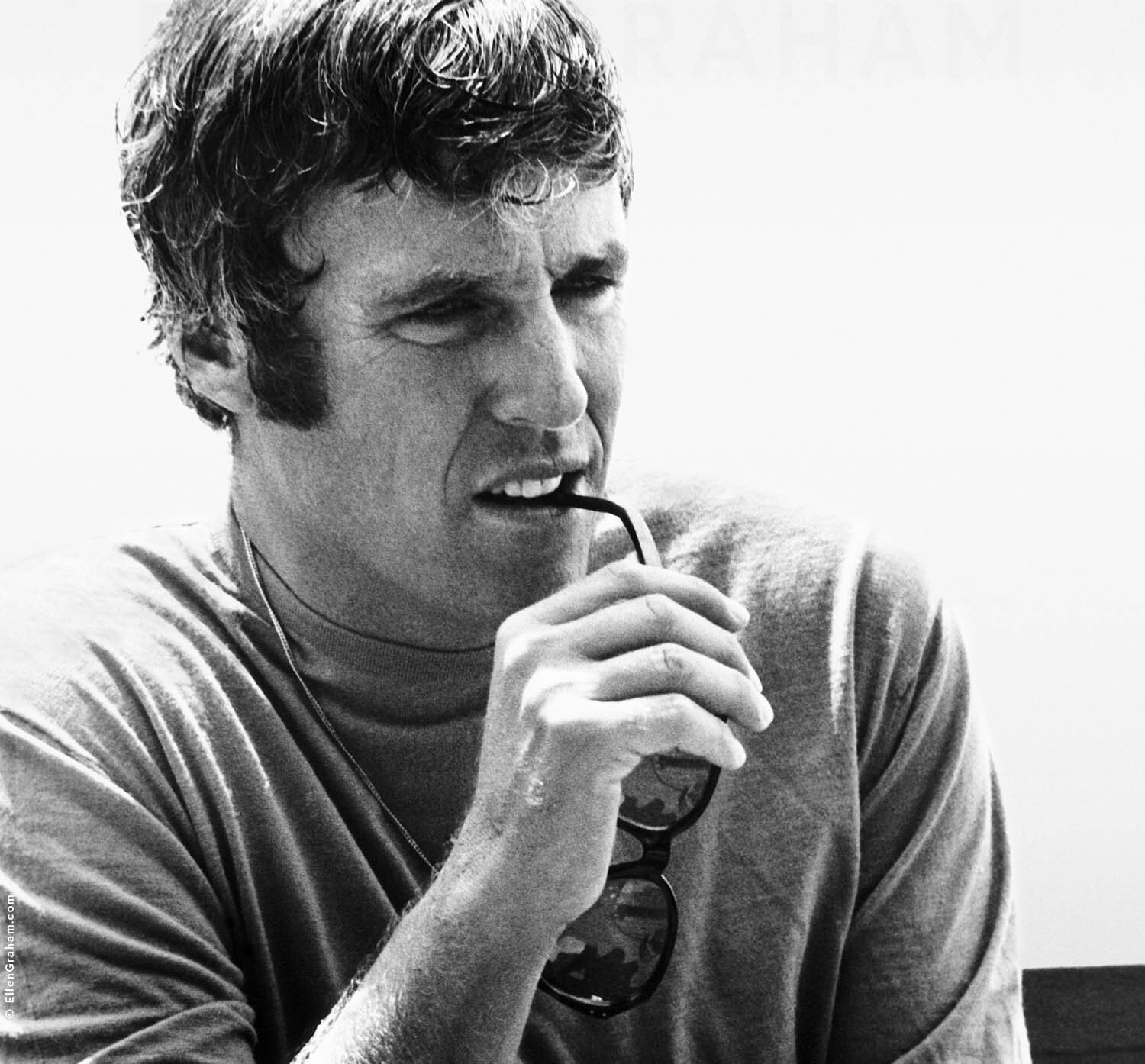

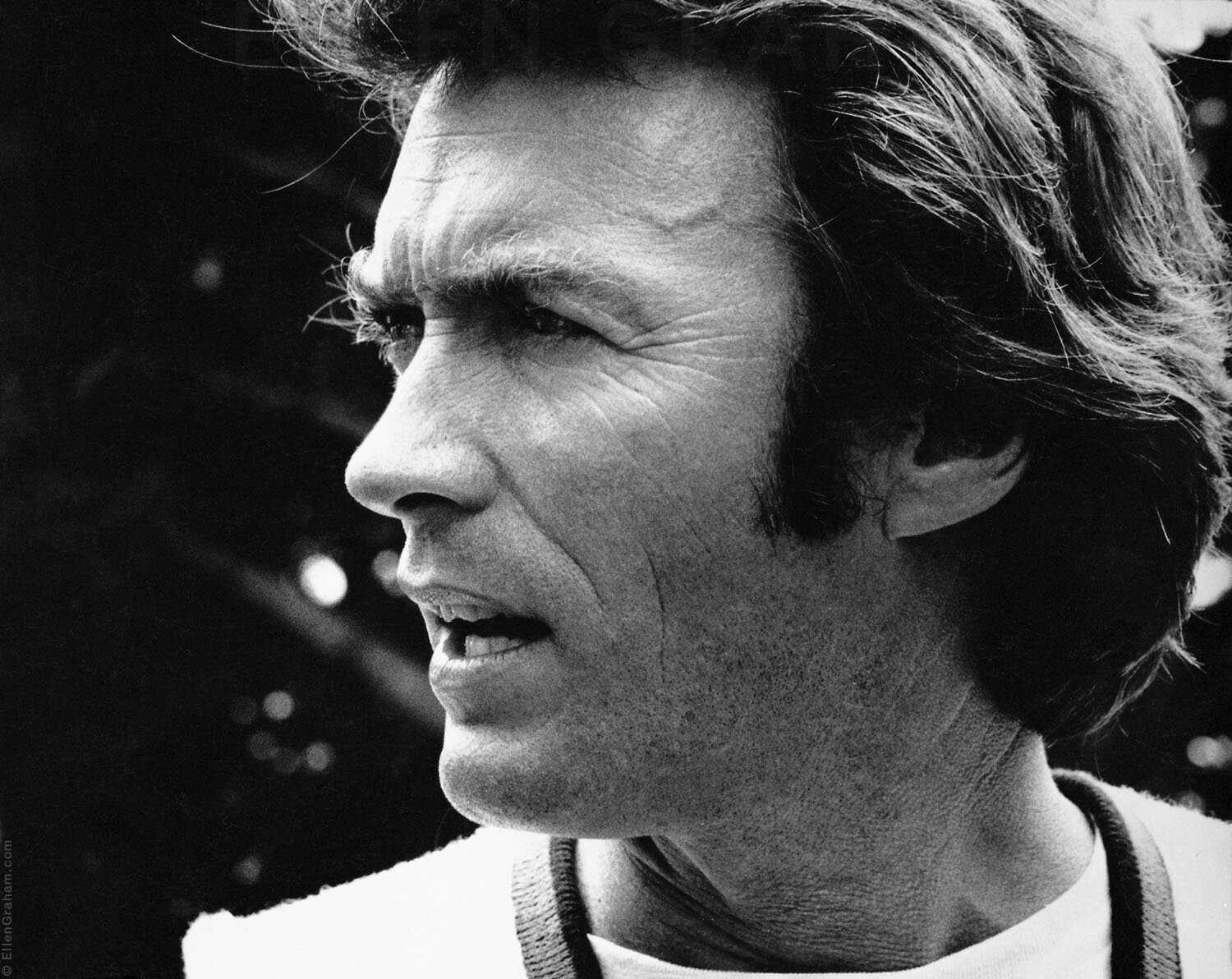

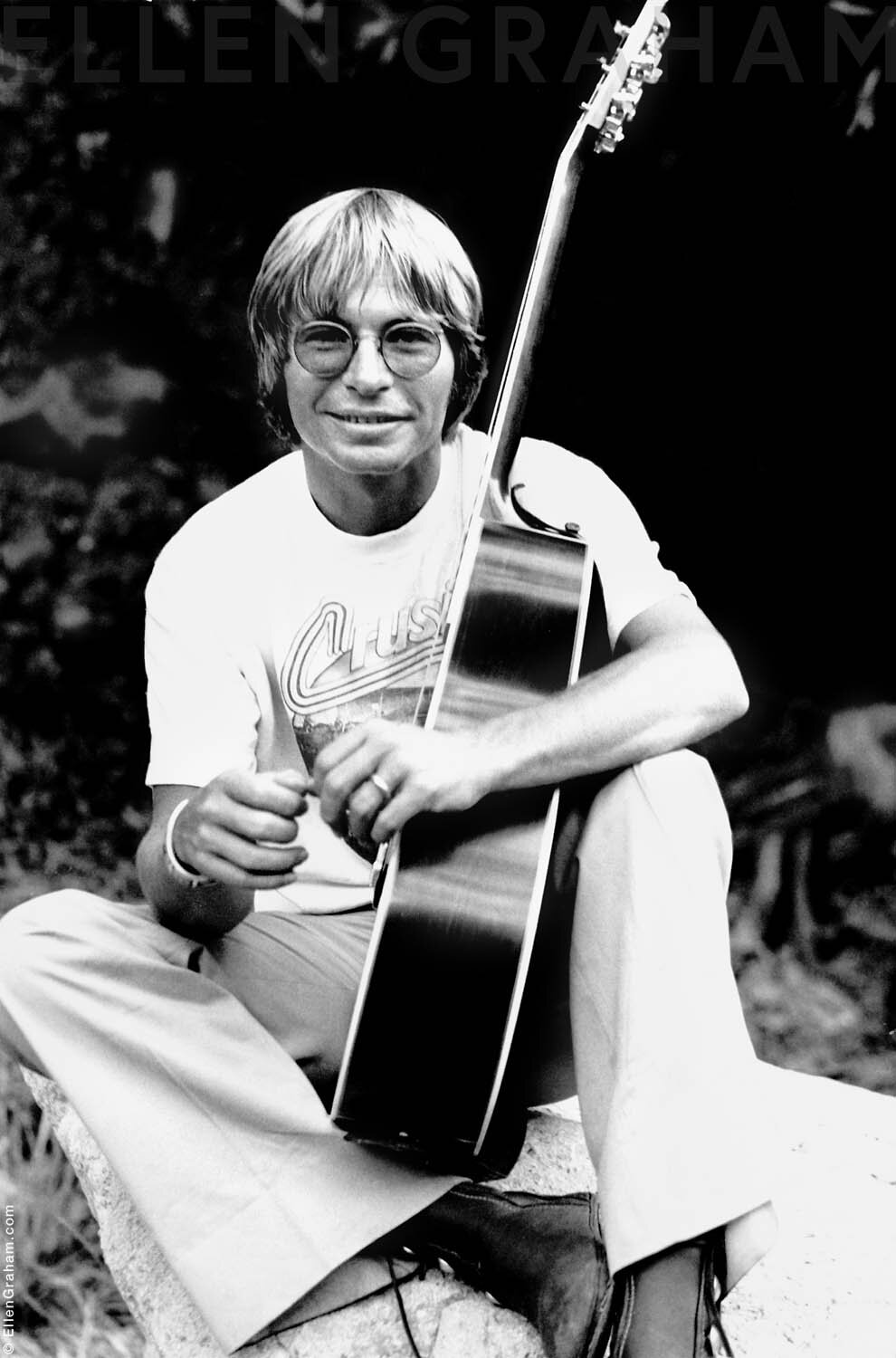

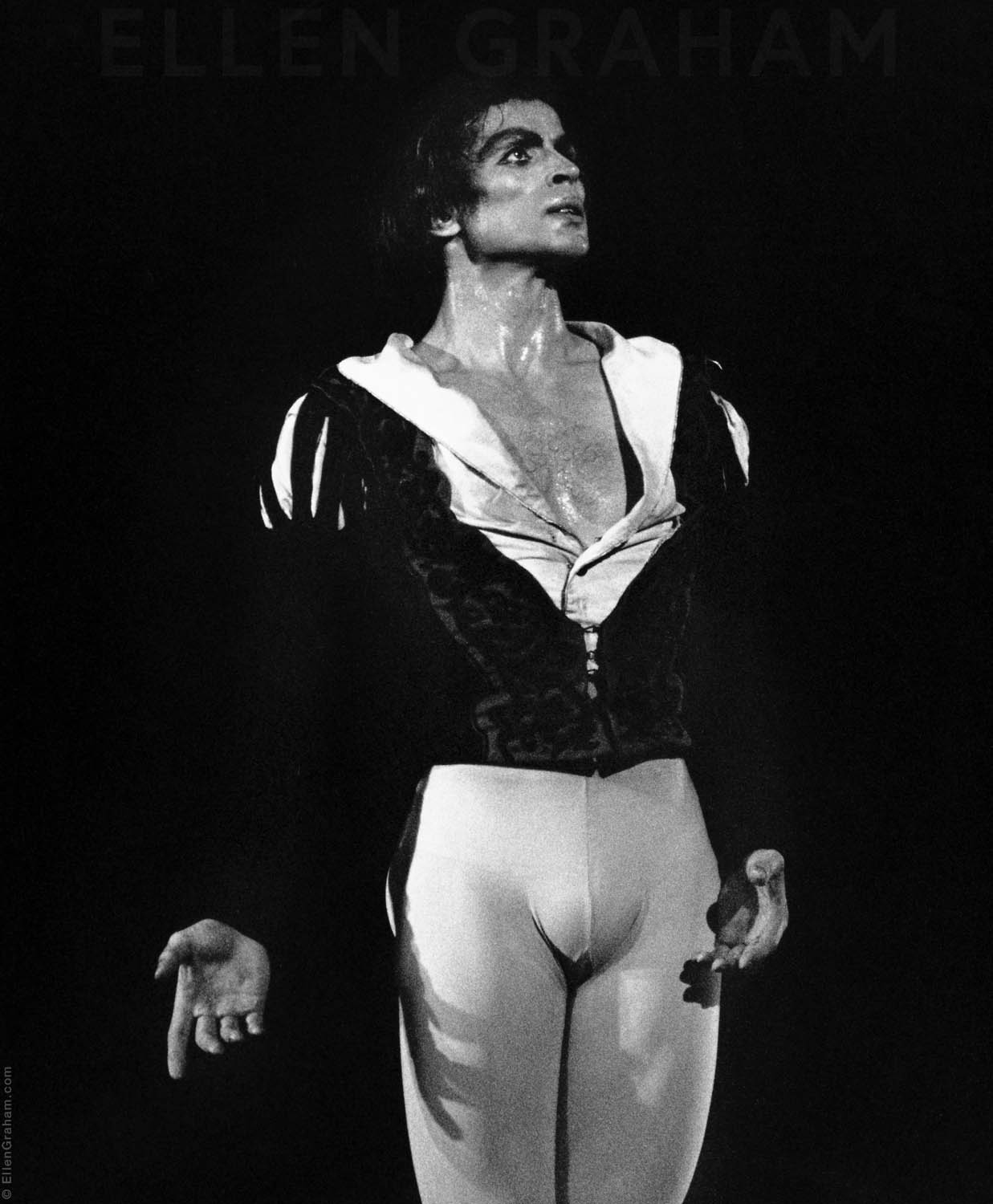

By the mid-1960s, Graham was embarking upon her first major editorial assignment. Men’s Bazaar had commissioned her to travel the globe, photographing “The World’s One Hundred Most Attractive Men.” From Hollywood stars like Warren Beatty, Clint Eastwood, Rock Hudson, and Steve McQueen to many other men of notable accomplishments in industries that include art, film, publishing, and fashion, Graham made portraits one on one, without the aid of any assistants.

She preferred working alone to maintain the relaxed, personal nature of the exchange between sitter and photographer. At the time, however, women photographers still had to confront many obstacles despite their early historical contributions to the medium. [4]

Graham has openly described the challenges — “hairy experiences,” [5] as one article terms them — she faced on a regular basis, including the inappropriate advances of several male subjects. One such incident is discussed in a 1979 article for the Los Angeles Herald Examiner:

... a male film star of the first magnitude who — in a rash moment during a sitting for Graham — suddenly removed all his clothes, except for an enormous necktie in an American flag pattern. Then, mostly in the buff, he paraded unashamedly (in fact, with unabashed macho pride) in front of the camera she’d set up on his Beverly Hills estate. The star smirked as the shutter clicked but threatened to sue when the work went on display several weeks ago in her one-woman show, “Shooting the Stars,” at Bloomingdale’s in Manhattan. [6]

As was true with this actor, many other male sitters Graham encountered either devalued her professional position, dismissed her expertise, or even reduced their session to what they assumed would be some sort of sexual exchange. Beyond fielding these passes, Graham faced societal expectations for women in America at midcentury.

In the same article — and seemingly unprompted — Graham points out that her alma mater “gave no tips on how to keep a marriage together when work becomes a 24-hour-a-day calling” and laments the difficulties of balancing her domestic responsibilities with her flourishing professional career. “Last night ... I burned the entire dinner. I was busy going over a proof sheet picking shots for prints and forgot the stove. Everything was ruined, including a couple of my husband’s favorite dishes ...” [7]

In an article highlighting her aptitude as a photographer, it doesn’t seem likely that the same pressures would be discussed with a male photographer. To pursue a professional photography career as a woman was in many ways to eschew the normative gender expectations of the period — perhaps an extension of the Kodak Girl. Although the height of Graham’s career occurred during a time of great cultural upheaval — the Women’s Rights Movement, second wave feminism, and the evolution of the feminist avant-garde — many barriers remained in place. Like so many women artists, Graham stayed focused on developing her practice, experimented with new ideas, and maintained several loyal clients including Gloria Swanson and Fred Astaire over the years.

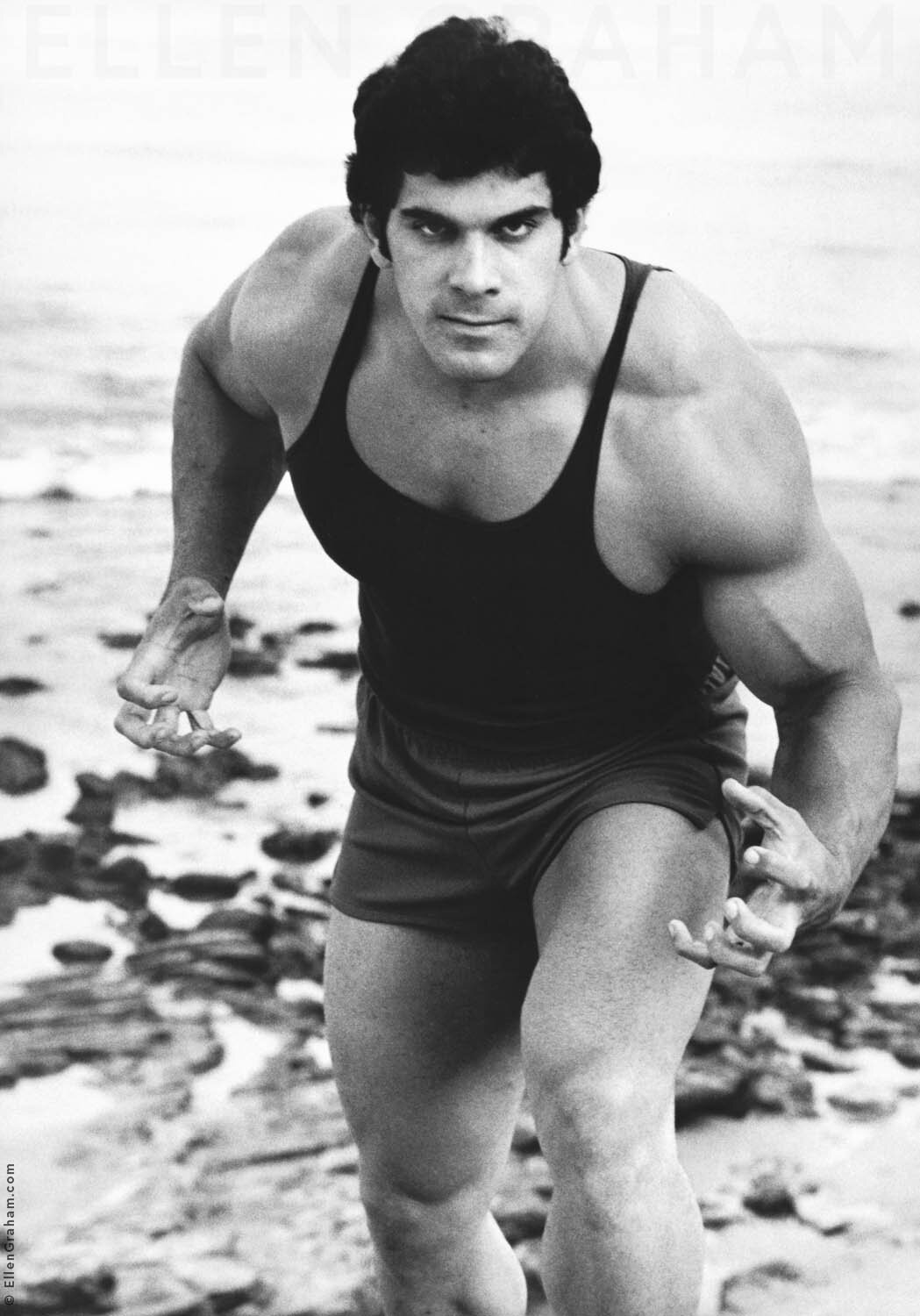

Following decades of celebrated portraits, a cheeky celebrity pet cookbook, [8] and innumerable editorial opportunities, Graham pursued her next project. Based on her first assignment for Men’s Bazaar, she would produce “an extraordinary international black and white photographic essay of exciting men. Their looks and thoughts, their feelings and relationships. With others and themselves.” [9] Graham had recognized a change in tide; with countless books focused on women and beauty, she proposed a coffee-table book that turned the camera toward male beauty, both inner and outer. Significantly, the book would function as more than “a series of pin-ups.” [10]

On the surface, Graham’s concept might read as merely a who’s who of celebrity men; however, what the book symbolizes is far more compelling. Graham, a woman photographer, sought to flip the paradigm and reverse the gaze, reflecting the values, attitudes, and reception of and by women. [11] Graham’s book project is a powerful, early, and commercial example of unearthing new conceptions of male identity and relationships.

Unfortunately, Graham never secured a publisher for Beautiful Men. She received at least thirteen rejection letters and, curiously, they all suggest the same ideas — that Graham is targeting a “very small, hard to reach market,” [12] that they “haven’t had much luck with this sort of thing,” [13] or, most telling, that “in the days of Dan Green, we could have done this and made it work, but now, forget about it — our sales reps would shriek.” [14] Dan Green, president of Simon & Schuster from 1984 to 1985 and 23-year veteran of the company, was responsible for convincing former GQ and Playboy columnist Charles Hix to create a book highlighting beautiful, athletic male bodies. [15] Working Out: The Total Shape-Up Guide for Men (1983) was a New York Times bestseller for 21 weeks.

Furthermore, it was Hix’s second bestseller; six years prior, he had published a male grooming guide called Looking Good that featured the then little-known photographer Bruce Weber’s sensual photographs of men. Graham even included Working Out as a key comparison for Beautiful Men; however, there was simply no market for photographs of men made by women, speaking to a broader double standard that permeated the field.

4) Women adopted photographic portraiture as early as 1890, making it one of the most highly paid occupations for women of the period. In subsequent decades, portraits became elevated to status symbols and women

were thought to possess unique intuition and emotional access that led to more successful images. See Naomi Rosenblum, A History of Women Photographers (New York, NY: Abbeville Press, 1994), 73-77.

5) Camilla Snyder, “Today is Culture: She shoots celebrities, doesn’t she?” Los Angeles Herald Examiner, August 28, 1979.

6) Ibid.

7) Ibid.

8) Ellen Graham, The Growling Gourmet (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 1976).

9) Ellen Graham, "Beautiful Men” (unpublished manuscript, June 1984).

10) Ibid.

11) Here, the gaze refers to the “male gaze,” a term coined by British feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey in her seminal 1975 essay, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” See Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” Screen 16, no. 3 (Autumn 1975): 6-18.

12) Unpublished rejection letter sent from Harper & Row Publishers, Inc., to Elaine Markson, Ellen Graham’s literary agent, on January 31, 1989.

13) Unpublished rejection letter sent from Crown Publishers, Inc., to Elaine Markson, Graham’s literary agent, on February 16, 1989.

14) Unpublished rejection letter sent from Simon & Schuster to Elaine Markson, Graham’s literary agent, on March 8, 1989.

15) Green proposed this in response to Simon & Schuster’s smash hit Jane Fonda’s Workout Book, which featured photographs of primarily women by Steve Schapiro. See Robert Dahlin, “Going in Reverse,” Publishers Weekly, May 22, 2023. www.digitalpw.com/digitalpw- refurl/20230522/MobilePagedArticle.action?articleId=1881909#articleId1881909.